This is part one of a nine-part series by documentary filmmaker Adam Halbur on the physician assistant model around the world.

View all posts in this series

- As Good As You Can: The PA Model Around the World Part One

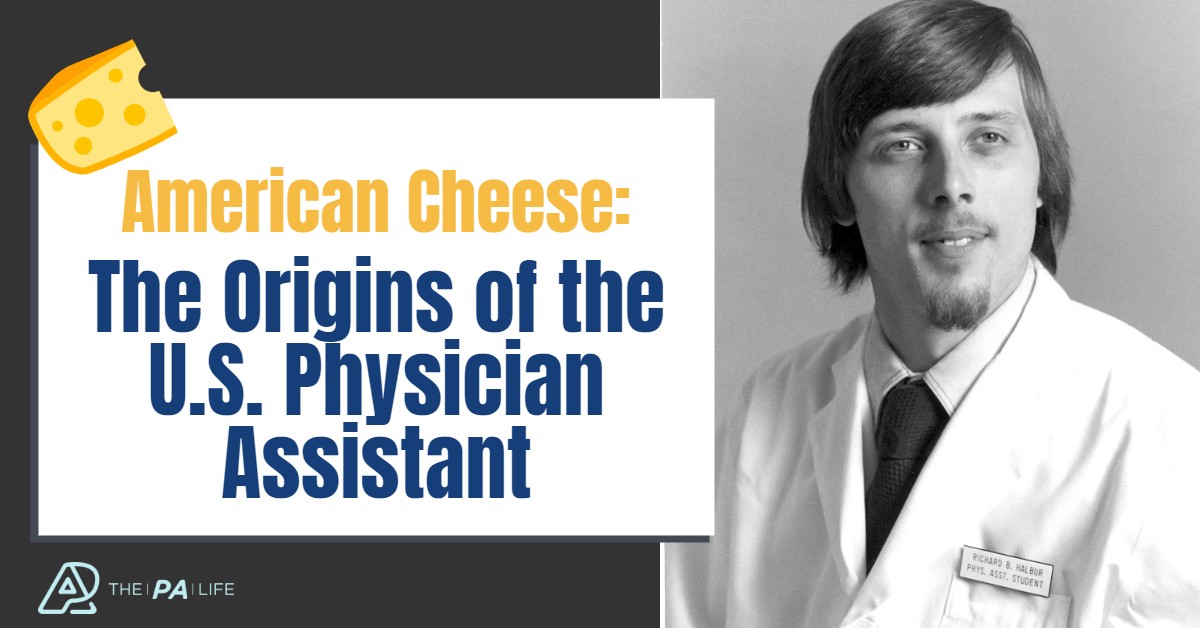

- American Cheese: The Origin of the U.S. Physician Assistant

- PAs in the Netherlands: The Dutch Physician Assistant

- Why We Really Need PAs in the UK: The British Physician Associate

- Meet The PA Pioneers of Israel: The Israeli Physician Assistant

- Trials and Tribulations of the Liberian Physician Assistant

- South Africa’s Clinical Associate (Clin-A): The PA Model Around The World

- The Indian Physician Assistant (PA): Past, Present, and Future

- The Australian Physician Assistant: The PA Model Around the World

- Laos: The Birthplace of the U.S. Physician Assistant?

- Little Big Men: The Rise of Kenya’s Clinical Officer

What do American Cheese and PAs Have in Common?

U.S. Patent 2759308, for the first American processed cheese wrapper, was submitted in 1956, and individually sheathed slices of imitation dairy started rolling out.

At the same time, the first PAs were getting their medical corpsman training and experiences during the war in former French Indochina, known now as Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, from 1955 to 1975.

By the late 1960s, small bands of PAs from a handful of programs were already beginning to practice in various specialties and capacities (see The Physician Assistant: An Illustrated History, Thomas E. Piemme MD, et al.). Accredited PA programs now number well over 250 and PAs well over 100,000.

In 2018, retail sales of American cheese were $2.77 billion, an impact reminiscent of the growth of canned food after the Civil War.

American cheese and the PA (albeit the latter being a little better for you) are two effects of militarism on U.S. society, and I am living proof--with “cheese” sandwiches on my childhood menu and Dad (PA number 180 in Wisconsin) my de facto childhood primary healthcare provider.

I do not mean to attack the PA character by such a comparison. Coming from the dairy state Wisconsin, I know something about good cheese, but I am not a medical professional nor an expert in the field; rather, I am a practiced poet and journalist who has turned to documentary work in search of ways to connect to people and connect people with each other in this globalized digital age.

I have found one such opportunity in the PA, who along with with the nurse practitioner, has more than one manifestation in the U.S and many more around the world, some existing before the U.S. model.

In 2017, I took the opportunity of the American Association of Physician Assistants’ 50th anniversary to film PA-like practitioners in nine countries, starting with my father, in his 40th year of practice, and Ruth Ballweg and David Kuhns, PAs of the same generation who have been instrumental in promoting, educating and networking PAs internationally.

Ballweg, a graduate and professor emeritus of the MEDEX program at the University of Washington, sat with me at the AAPA conference in Las Vegas, to relate PA history and her advocacy, especially in the Asia-Pacific region.

A successor to Dr. Richard Smith, who got many of his ideas for the MEDEX program from work with similar practitioners in Africa, Ballweg considers PAs necessary to developing countries like South Africa (clinical associates) and India (physician assistants) to compensate for the brain drain of physicians to the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia, stating“About 40 percent of the doctors in our country are trained overseas.”

And she considers PAs necessary to developing and developed countries alike to provide better care.

Ballweg’s colleague Kuhns is one of the first PAs lucky enough to have worked with Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors without Borders), first in Somalia and then in Afghanistan after boosting his résumé with a master’s in public health.

The experience left him with PTSD and exasperated by his American patients.

Kuhns believes the public needs to be better educated and more responsible for the state of their own health.

And yet for him, the U.S. privatized healthcare system could learn from the public systems of Ireland and the U.K., where he advised burgeoning programs and helped train some of their first PAs (physician associates).

With the PA’s ability to cut costs and provide quality care, Ballweg and Kuhns spoke favorably of a national system for the U.S.

American PAs have streamlined health care (more or less as American cheese has streamlined fast food), and this, according to my father, is why the profession has been successful.

The main profiteer from lower practitioner overhead in the U.S. remains the healthcare industry, including pharmaceutical companies, which my father referred to as wasteful and not very helpful at times in their practices to market new products when older ones remain cheaper and work just as well or better.

Then there are the insurance companies, which have raised premiums as much as 20 percent per annum while attempting to deny reimbursement for covered items, so that not only do many citizens not have equal access to the highest quality medical treatment, some often have to be ever-vigilant over what they have purchased.

Part of the obstacle to national care is resentment among the general public. We do not have to like our neighbors, but we do not have to spite them.

On my way to an interview in Canada, where they are starting to use PAs to reduce costs in their public system, I stopped in an Indiana bar. Here, I met a retiree, a beneficiary of advanced cardiac care, who said his daughter was a PA and who in the next breath voiced his opposition to a national health plan because he was covered already by his union.

Perhaps we should view birth into the human race as admission into the union, which benefits its members whether they work hard or not, make a little money or a lot, and deserve to have a porcelain throne or just a pot.

There is only so much a person can do in a day.

PAs are some of the hardest-working best-compensated professionals in the U.S., but we can’t all be PAs. Or we can, but like poets, who would need them then? And what will happen if PA supply ever outstrips demand? And what will be the effects of AI?

At present, the PA profession in the U.S. continues to be one of the more accessible and immediately rewarding ways to get into medicine, and with the profession's continued demand by the industry and rising salaries highlighted in Forbes over the past years, competition for U.S. PA school admission is tight.

Contessa, a second-year PA student in Oregon and my father's preceptee at the time, describes her experience:

Patients demand PAs, too. Citing PA dedication (not just handing out pills) and affability (the ability to communicate), one of my father’s regulars exclaimed, somewhat cheesily, “They will save your life!” Though, with Dad sitting in the same room, you could hardly expect them to be impartial.

My father, in fact, never wanted to be a PA. He got his start in the early 70s when he joined the U.S. Air Force as a corpsman to avoid being drafted and then sent to Vietnam.

He ended up at Anderson Air Force Base, Guam, watching the last bombing runs take off and return, and at the now-defunct Tachikawa Air Force Base, Tokyo, Japan, where you could already get a McDonald’s cheeseburger in those days.

Before being talked into considering the PA profession, he had hoped to become a full-fledged physician, a superhero, and still harbors some regrets for not following through with that dream. He has been quite fortunate with the choice he made, but listening to him and other PAs on my journey, perhaps there should be opportunities for them to advance to physician roles based on proven experience and continuing education.

Humans are, after all, not uniform products, but constantly seeking to exceed their limits.

The second installment of this blog series, “The Anatomy Lesson,” will consider the PA in the Dutch public healthcare model.

Adam Halbur is a writer and teacher living in Tokyo, Japan. A short version of his film As Good As You Can, As Professionally As You Can premiered at the 11th annual conference of the International Academy of Physician Associate Educators. Watch the “American Cheese” segment of the longer version here. Watch a short of the 50th AAPA Conference with interviews from Ruth Ballweg and David Kuhns here. Halbur is entirely self-funded, so if you appreciate his work, please consider making a small contribution to his feature documentary on the Kenyan clinical officer.

Resources and references

- https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/5e/60/46/85702e75801611/US2759308-drawings-page-1.png

- https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/7b/f3/1f/74eac5574c98f8/US2759308-drawings-page-2.png

- https://www.amazon.com/Physician-Assistant-Illustrated-History/dp/1935089641

- http://www.arc-pa.org/accreditation/accredited-programs/

- https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-10-10/american-cheese-is-no-longer-america-s-big-cheese

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/brucejapsen/2018/05/23/physician-assistant-pay-surpasses-107k-annually/#16250968762c

- https://mosthustleanddesire.github.io/as_good_as_you_can/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dgr42W1zeLM&t=372s

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aH0h9heJVTM

View all posts in this series

- As Good As You Can: The PA Model Around the World Part One

- American Cheese: The Origin of the U.S. Physician Assistant

- PAs in the Netherlands: The Dutch Physician Assistant

- Why We Really Need PAs in the UK: The British Physician Associate

- Meet The PA Pioneers of Israel: The Israeli Physician Assistant

- Trials and Tribulations of the Liberian Physician Assistant

- South Africa’s Clinical Associate (Clin-A): The PA Model Around The World

- The Indian Physician Assistant (PA): Past, Present, and Future

- The Australian Physician Assistant: The PA Model Around the World

- Laos: The Birthplace of the U.S. Physician Assistant?

- Little Big Men: The Rise of Kenya’s Clinical Officer

Leave a Reply